Should tracing the source of the E. coli O157:H7 in lettuce be a top priority?

Almost three months after the outbreak started, consumers, the food industry, the government agencies (CDC and FDA) are getting antsy because the source of contamination for the E. coli O157: H7 in lettuce is still unknown. Most of the focus is currently on traceability. Should the focus be there?

Almost three months after the outbreak started, consumers, the food industry, the government agencies (CDC and FDA) are getting antsy because the source of contamination for the E. coli O157: H7 in lettuce is still unknown. Most of the focus is currently on traceability. Should the focus be there?

The human toll

This outbreak took a huge human toll. According to an update by the CDC by now, 197 people from 35 states were infected with the outbreak strain of E. coli O157:H7. 48% of them have been hospitalized, including 26 people who developed hemolytic uremic syndrome; five deaths have been reported from Arkansas (1), California (1), Minnesota (2), and New York (1).

The CDC emphasizes that most of the newly reported cases involve people who fell ill two to three weeks ago, when contaminated lettuce from the Yuma, Arizona, area was still available to consumers. Some people also got sick after “close contact” with infected individuals. It is important to accentuate that most people got sick before the CDC announcement not to eat romaine lettuce from Yuma.

The economic Toll

Beyond the human suffering, the E. coli outbreak caused enormous losses to growers, retailers, and disrupted supply chains as restaurants scrambled to find romaine lettuce alternatives. “During the week of April 14 (the week the news broke), romaine dollar sales fell 20%, which pushed total lettuce performance down by double digits: iceberg lettuce dollar sales were down 19%; red leaf lettuce dollar sales fell 16%; and endive dollar sales dipped 17%,” according to a Nielsen report on National Salad Month.

In May, Romaine sales fell nearly 45%, according to the WSJ, iceberg fell 22%, and red leaf fell 17%. Prices for whole heads of romaine lettuce were down 60%. This deadly outbreak had shaken consumer’s confidence in leafy greens and especially lettuce, resulting in millions of dollars of losses for growers, retailers, and restaurants.”

The letter from consumer groups to FDA

After two outbreaks of E. coli O157: H7 in lettuce, that both went unsolved, 9 consumer and food safety groups (Center for Foodborne Illness Research & Prevention; Center for Science in the Public Interest; Consumer Federation of America; Consumers Union; Food & Water Watch: National Consumers League; The Pew Charitable Trusts; STOP Foodborne Illness; and the Trust for America’s Health.) wrote a letter to FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb In the letter, the organizations demand that FDA should add regulations within the next six months “for comprehensive and rapid traceability of produce, including leafy greens.”

In the letter they claim that existing recordkeeping requires only “one step forward, one step back” records that result in “tangled web of inconsistent and inadequate” information for those tracking outbreaks. They claim that “Part of the purpose of this (FSMA) landmark legislation was to enhance traceability in the event of an outbreak of foodborne illness, allowing the FDA to trace back illness to its source and implement swifter and more accurate recalls.” “The repeated outbreaks linked to produce and leafy greens since passage of FSMA leave no doubt that these products belong in the “high-risk” category. “

The primary focus of this letter is an improvement of traceability of the lettuce suggesting blockchain as one of the options.

FDA effort to trace the source

On May 31, Scott Gottlieb, M.D. Commissioner of the FDA, and Stephen Ostroff, M.D FDA’s Deputy Commissioner issued an update on the traceback efforts to find the source of the E. coli O157:H7. This investigation includes the study of the multiple steps (suppliers, distributors, and processors cutting the lettuce, and bagging it). It starts at the farm and ends at the bags, attempting to accurately follow the pass of the contaminated lettuce to the supermarket, restaurant or other location where it was sold or served to consumers that got sick.

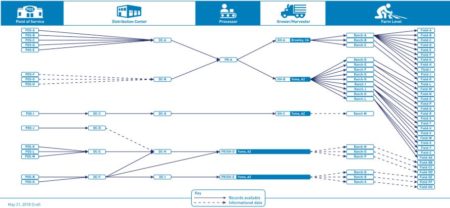

The traceback efforts intend to find points of convergence from several well-identified clusters of illness with a common point of exposure, such as a supermarket or restaurant. A line is drawn for each cluster from one point in the supply chain to another point. Intersections in the line can lead back to a common location that might be the source of contamination.

As can be seen in the diagram below there are no obvious points of convergence along the supply chain. The exception is whole head lettuce served in the Alaska correctional facility (see the middle of the chart). The reason for the easy traceback is that it was not processed and was not mixed with lettuce from multiple farms.

Figure 1: traceback diagram for FDA investigation of multistate outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 infections linked to romaine lettuce from Yuma growing region.

The data indicates that there is no simple explanation on how the outbreak occurred. It also indicates that the contamination happened in the Yuma growing area and not later. They speculate that “contamination occurred on multiple farms at once, through some sort of environmental contamination (e.g., irrigation water, air/dust, water used for pesticide application, animal encroachment).” Dr. Gottlieb and Dr. Ostroff acknowledge that the source of contamination might be challenging to find.

Is blockchain and traceability the solution?

As explained in a previous blog a bag of lettuce might contain pieces of lettuce from more than one farm, making tracing a piece of lettuce to a particular farm very difficult. The efforts by FDA to trace back to the source demonstrate the challenges.

Even if we had a perfect traceback system, it might not have helped significantly in preventing the outbreak. Since it takes a couple of weeks to identify that there is an outbreak, by the time that CDC and FDA realized that there is an outbreak related to lettuce most of the ill people had already consumed the product.

“If they (FDA) know the points of sale, why not say so,” said William Marler. According to Bill Marle “there are at least four separate clusters, the one in Alaska linked to Harrison Farm, one on the East Coast linked to Panera Bread and Freshway, and two on the West Coast linked to Papa Murphy’s and Red Lobster.” He is working to file lawsuits against the place of purchase of the contamination of the romaine to force the disclosure of distributors that sold the contaminated lettuce.

Where to Focus?

A new task force has been initiated to improve food safety around leafy greens, Scott Horsfall, CEO of the California Leafy Greens Marketing Agreement and a member of the task force steering committee said: “There’s been a recognition that the industry … and the science community and all the stakeholders in this effort need to come together again and take a good, hard look at everything that is available and see if we can’t figure out what steps can be taken so that we reduce the risk of this kind of thing happening again,” he also quoted Horsfall. “I would say that we’re going to focus heavily on practices that are going to prevent illnesses in the future because traceback and the investigation often just take a long time, so far better if we prevent the pathogens from ever getting in the marketplace.”

Perhaps scientists from academia, farmers, and other experts from all over the country should be tasked with solving the contamination problem rather than merely the traceability issue.