Romaine Lettuce: The FDA Dilemma to Recall or Not and When to Recall

Where are we today?

According to the Center of Disease Control (CDC) the outbreak due to E. coliO157:H7 that started in March of 2018, involves a total of 129 people. Sixty-four (50%) of them have been hospitalized, and one death.

A very troubling aspect of this outbreak is that 17 of those sickened have developed hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). The extremely high number of hospitalization for the outbreak and the high number of HUS patients is because the E. coli O157:H7 produces Shiga toxin type 2 (STX2). The Shiga toxin type 2 binds to the lining of blood vessels in the kidneys, digestive system and brain, making it particularly dangerous. This is the same type of strain associated with the 2006 outbreak linked to fresh spinach.

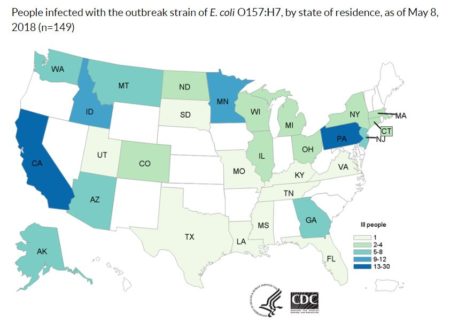

The outbreak was seen in 29 states including: Alaska (8); Arizona (8); California (30); Colorado (2); Connecticut (2); Florida (1); Georgia (5); Idaho (11); Illinois (2); Kentucky (1); Louisiana (1); Massachusetts (3); Michigan (4); Minnesota (10); Mississippi (1); Missouri (1); Montana (8); New Jersey (8); New York (4); North Dakota (2); Ohio (3); Pennsylvania (20); South Dakota (1); Texas (1); Utah (1); Virginia (1); Washington (7); and Wisconsin (2). Additionally, six are reported ill in Canada.

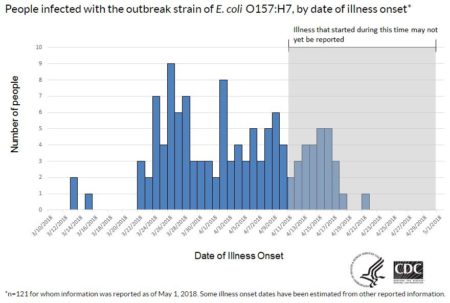

On average it takes 2-3 weeks between when a person becomes ill with E. coliuntil the data is recorded by the CDC. Therefore illnesses that occurred after April 17, 2018, might not yet be reported.

Ill people were interviewed by state and local health officials, and 91% reported eating romaine lettuce in the week before they became ill. While CDC does not seem sure about the exact location of the lettuce that is causing the disease, the current information suggests that romaine lettuce from the Yuma AZ growing region could be the source of the outbreak with E. coli O157:H7.

The romaine lettuce outbreak is the largest multi-state E. coli outbreak in the U.S. in a decade.

According to the CDC, the current outbreak is unrelated to the multi-state outbreak of E. coli in leafy greens in November and December of 2017, because the two strains of E. coli O157:H7 bacteria have different DNA fingerprints.

The Lawsuits are coming

Louise Fraser, a 66-year-old woman, was one of the first victims of the romaine lettuce outbreak. She was sickened by the outbreak E. coli stain after apparently eating contaminated romaine lettuce at Panera Bread Co in New Jersey.

Marler Clark is representing 64 individuals affected by the outbreak. Several customers of Panera Bread in Missouri, New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania and at least three Texas Roadhouse customers in Georgia all got sick with a genetically linked strain of the bacterial infection. Ten of the people filing lawsuits have developed HUS. According to his website, Marler Clark filed the first lawsuit against Freshway INC. The supplier for Panera Bread in New Jersey. Two additional lawsuits were filed one in Pennsylvania against Freshway and a third in Arizona against Red Lobster.

Yuma season was over by mid-April

Yuma supplies 90% of US greens in the winter. However, according to the Arizona Department of Agriculture and the Arizona Leafy Greens Marketing, the romaine harvest season in the Yuma area ended on April 13, 2018. The production of romaine lettuce has shifted since to Salinas CA and adjacent areas.

However, due to the 21-day shelf life, the FDA cannot be certain that romaine lettuce from Yuma is no longer in the supply chain. Nevertheless, it appears that the tainted lettuce has passed its expiry date.

While the product was not recalled the CDC advises consumers not to eat romaine lettuce unless they are confident it does not come from the Yuma, AZ. The CDC recommends to restaurants not to serve romaine lettuce unless they are sure its source is it outside the Yuma area.

The new cases being found now are due to the delay between eating the contaminated product and recording the illnesses in the CDC.

Why is it difficult to pinpoint the source of the outbreak?

Federal investigators first warned of the E. coli problem in April after people started getting sick from greens that they ate on March 22 to 31 in Panera Bread in NJ. Now, seven weeks later, the federal investigation led by the FDA has not been able to pinpoint which romaine fields are causing the outbreak. The Investigators are looking at “dozens” of farms as possible sources.

So far the only source for the outbreak found is the Harrison Farms, which supplied whole-head romaine lettuce to a correctional facility in Alaska, sickening eight people. Those heads were harvested between March 5 and 16 and are past their 21-day shelf life.

Below is a schematic flow diagram of the lettuce processing that can demonstrate why the product can be so variable in its microbiological content.

As the lettuce grows in the field (A) it is subject to contamination by birds, domestic and wild animals. Such contamination can be on some of the lettuce heads and not others. (B) The quality of the irrigation water varies. In the harvesting step (C) sanitary conditions of the workers can contribute to the contamination. The boxed lettuce is loaded on a truck (D), in many cases, the truck carries boxes from several farms. In the processing plant (E) the lettuce gets mixed. The process does not stop necessarily between farms. As the lettuce get cut and washed (F) further mixing of the lettuce pieces can occur. Therefore in the finished bag, there might be pieces of lettuce from more than one farm.

This simplistic figure shows how complex it can get in trying to find the origin of an outbreak.

What happens when a recall is done prematurely?

In 2008, one of the most significant foodborne outbreaks erupted, were more than 1,400 people in 43 states got ill from Salmonella Saintpaul. Raw tomatoes were implicated early on, eventually epidemiologic and microbiologic evidence implicated jalapeno and Serrano peppers from Mexico, as the cause of the outbreak.

The reason that early in the investigation, raw tomatoes were thought to be the cause was that there was a strong association between illness and consumption of raw tomatoes. Acting on the early information, without completing the investigation, the FDA warned consumers not to eat tomatoes. Consumers began avoiding tomatoes. Stores removed tomatoes from their shelves, and restaurant customers started ordering their customary dishes without tomatoes

FDA may have unwittingly allowed the outbreak to continue by prematurely jumping to the conclusion that tomatoes were causing the outbreak. The tomato industry suffered the loss of their crops and a loss of profits with the ban costing tomato farmers hundreds of millions of dollars.

Overall, the FDA tomato warning is an episode both the tomato industry and the FDA wish never happened.

Final thoughts

The CDC concluded that slightly over half (51%) of outbreak-related illnesses were attributable to plant commodities, with 42% and 6% being assigned to land animal and aquatic animal commodities, respectively. Produce (fruits-nuts and five vegetable commodities) accounted for 46% of illnesses, and meat-poultry products accounted for 22%.

The current outbreak is the biggest Shiga-toxin E. coli outbreak since the 2006 outbreak caused by spinach grown in the Salinas Valley in California. Both outbreaks were caused by an STX2-only E. coli. The spinach outbreak was traced to a particular grower. The field was located near a stream were cattle and wild pigs resided. It might not be possible to identify the source of the current outbreak.

In the current outbreak due to Romaine lettuce from Yuma, the CDC issued a series of alarming statement to the public advising consumers to stop eating Romaine lettuce in any form. However, since the source was not identified the FDA did not issue a recall. The Yuma season was over before most of the announcements in the media were made.

While it is likely that more cases will turn up as the outbreak is coming to an end, and the lettuce in stores is most probably safe.