Food Fraud- Prevalence, Current Status, and Mitigation

What is Food Fraud

Many cases of food fraud are reported both in the US and around the globe. For example, a year ago there were many reports about Parmesan cheese that contained fillers like wood pulp, cellulose, and cheddar. In Europe horse meat was labeled as beef.

Many cases of food fraud are reported both in the US and around the globe. For example, a year ago there were many reports about Parmesan cheese that contained fillers like wood pulp, cellulose, and cheddar. In Europe horse meat was labeled as beef.

There is no universal definition of food fraud. The U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention maintains a Food Fraud Database and describes food fraud as a “deliberate substitution, addition, tampering or misrepresentation of food, food ingredients or food packaging, or false or misleading statements made about a product for economic gain.”

Michigan State University in its Food Fraud Initiative defines it as “a collective term used to encompass the deliberate and intentional substitution, addition (or dilution), tampering, or misrepresentation of food, food ingredients, or food packaging; or false or misleading statements made about a product, for economic gain.”

In most cases, when discussing food fraud we refer to EMA (Economically Motivated Adulteration). It involves misrepresentation of the true nature of a food product or ingredient. The goal of the seller is economic gain.

Major Types of Food Fraud

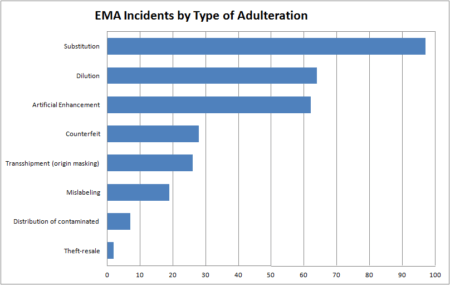

The National Center for Food Protection and Defense at the University of Minnesota has identified the following eight types of EMA:

Substitution involves complete replacement of a food product or an ingredient with an alternate product or ingredient. Examples include extra virgin oil substituted with oil of a lower cost such as regular olive oil or diluted with soybean oil and substituting higher value fish with lower cost, more abundant fish.

Dilutioninvolves partial replacement of a food product or ingredient with an alternate ingredient. Examples include dilution of honey with sugar syrups, olive oil with other oil, and the addition of horse meat to ground beef.

Artificial enhancement is the addition of unapproved chemical additives to enhance the perceived quality of a product. Examples include the addition of Sudan dyes to chili powder and the addition of melamine to milk.

Counterfeit is fraudulent labeling of a product by an unauthorized party as a brand-name product. Examples include counterfeit infant formula and counterfeit Heinz ketchup bottles.

Transshipment or origin masking refers to misrepresentation of the geographic origin of a product to avoid import duties, regulatory oversight, or to benefit from consumer demand. Examples include routing Chinese honey shipments through Vietnam to avoid U.S. import duties and mislabeling imported shrimp as U.S. Gulf coast shrimp.

Mislabeling refers to misrepresentation with respect to harvesting or processing information. Examples include misrepresentation of label information for organic produce, cage-free eggs, kosher foods, halal foods, and date-markings.

Intentional distribution of a contaminated product is the intentional sale of a product despite knowledge of foodborne contamination. Examples include the intentional sale of Salmonella contaminated peanut products and the intentional export of dioxin-contaminated fish.

Theft and resale refers to situations where a food product has been stolen and re-enters into commerce through unapproved channels. Examples include retail theft of infant formula and cargo thefts.

From the Food Protection and Defense Institute (FPDI) the following graph was generated to show the prevalence of each categories of adulteration.

Impacted FOODS

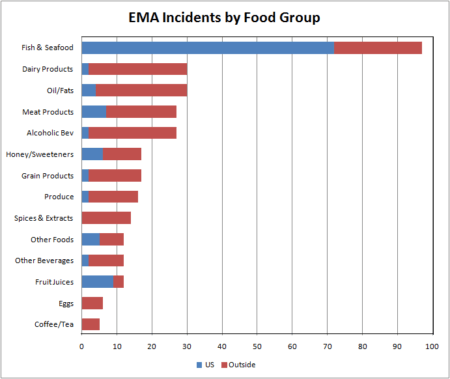

The most common foods involved in fraud, in order of prevalence are:

Fish and seafood: The most common type of products being adulterated are seafood products. According to a study by Oceana the highest mislabeling rates are for fish sold as snapper (87%) or tuna (59%), with the majority of the samples identified by DNA analysis as something other than what was found on the label. Only seven of the 120 samples of red snapper purchased nationwide were actually red snapper. The other 113 samples were other fish.

Dairy Products: Cow milk can have milk from other types of animals such as sheep, buffalo, and goats-antelopes, added to it. It can be adulterated with reconstituted milk powder, urea, and rennet, among other products (oil, detergent, caustic soda, sugar, salt, and skim milk powder). Adulterated milk may also be watered down and then supplemented with melamine to artificially raise the apparent protein content and hide dilution.

Oils and Fats: Almost 70 percent of extra virgin olive oil is said to be adulterated, the oil is often substituted or mixed with lower cost alternatives oils such as soybean, corn, peanut, sunflower, etc.

Meat Products: Meat product fraud comprise of the majority of EU fraud. It includes the replacement of high values species with lower value species and dilution of product with water. In 2013, consumers in England, France, Greece and several other countries were defrauded and unknowingly purchased meatballs, burgers and other food products that contained horse meat.

Honey: Honey might have added sugar syrup, corn syrup, fructose, glucose, high-fructose corn syrup, and beet sugar, without being disclosed on the label. Honey from a “non-authentic geographic origin” is also common, e.g., where honey from China is transshipped through another Asian country and falsely sold as honey from the second country—usually to avoid higher customs duties and tariffs that would be imposed on honey from China.

A number of other products such as Fruit Juice might be watered down, or a more expensive juice (such as from pomegranates) might be diluted with a cheaper juice (such as apple or grape juice). Coffee and tea e.g. ground coffee may contain roasted corn, ground roasted barley, and roasted ground parchment.

From FPDI the following graph was generated to show the prevalence of fraud in each food type.

Economical Impact

According to a 2014 report by the Congressional Research Service, it is estimated that up to 10% of the food supply could be affected by food fraud. Thus, the costs of fraud food are borne by industry, regulators and, ultimately, consumers. It is estimated that economically motivated adulteration (EMA) of food, or food fraud, costs the food industry $30–40 billion per year.

According to Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA) the estimated food fraud costs the world economy $49 billion annually.

“The impact on any particular company can range from minor economic damage to the potential loss of economic viability of the organization”, said Shannon Cooksey, vice president of science policy & regulatory affairs for GMA. “GMA joined with Battelle, the world’s largest non-profit R&D organization, to develop a better way of prioritizing the actual risks to specific commodity supply chains at any time, so that decision makers can best apply their resources to the vulnerabilities of greatest importance.”

How to Prevent it- the FSMA Effect

The preventative control rule of FSMA published in September 2016, addresses EMA (Economically motivated adulteration) when there is a reasonable possibility that adulteration could result in a public health hazard. This rule requires mitigation (risk-reducing) strategies for processes in certain registered food facilities.

The FDA guidelines require that each covered food manufacturing facility prepare and implement a food defense plan. The plan must identify:

- Vulnerability assessment: This is the step of identification of vulnerabilities and determining actionable processing steps. It includes the identification of the severity and scale of the potential impact on public health. Reviewing and assessing various factors, which create vulnerabilities in a supply chain (i.e. weak points where fraud has greater chances to occur).

- Mitigation strategies: Measure taken to decrease vulnerability to a certain type of adulteration in the supply chain. The steps are implemented at each actionable processing step to provide assurances that vulnerabilities will be minimized or prevented.

- Mitigation strategy management components: Steps must be taken to ensure the proper implementation of each mitigation strategy. Establishing and implementing procedures for monitoring the mitigation strategies. Corrective actions implementation. Verification activities that ensure that monitoring is being conducted and appropriate decisions about corrective actions are being made.

- Training and recordkeeping: Facilities must ensure that personnel assigned to the vulnerable areas receive appropriate training; facilities must maintain records for food defense monitoring, corrective actions, and verification activities.

It is important to validate and verify that mitigation measures are working, and continually review food fraud management system. A guideline for step by step assessment is available at U.S. Pharmacopeia . Assessing the risk of fraud for a food ingredient requires the understanding of the inherent raw material vulnerabilities, the business vulnerabilities, and establishing the appropriate controls. This will allow to define which preventive actions are needed (and where) to mitigate the risk of food fraud. The vulnerability assessment is not a onetime activity but a dynamic continuous process.

One response to “Food Fraud- Prevalence, Current Status, and Mitigation”

discount louis vuitton bags

It is also worth noting that the printing technology also uses cotton fiber certified by the Better Cotton Initiative or Global Organic Textile Standard, which is also a very useful renewable resource fiber. At the same time, Original Women louis Vuitt…